A growing body of research is reshaping how the public understands dementia, challenging the long-held belief that the condition is largely unavoidable. Instead of being driven purely by genetics or fate, experts now say that a substantial share of dementia cases could be delayed—or even prevented—through simple, consistent lifestyle changes.

The scale of the issue is stark. One in three people alive today is expected to develop some form of dementia during their lifetime. Even more troubling, only around a third of those currently living with the condition have received an official diagnosis. That gap leaves millions without access to treatment, support, or planning tools that could improve their quality of life.

Recent headlines have brought renewed attention to the illness after Britain’s youngest known dementia patient died at just 24 years old, only two years after being diagnosed. The tragedy highlighted how indiscriminate and devastating dementia can be, affecting not only the elderly but, in rare cases, people barely into adulthood.

Against this backdrop, a leading neurological specialist appeared on national television to deliver a message that surprised many viewers: nearly half of dementia cases may be preventable.

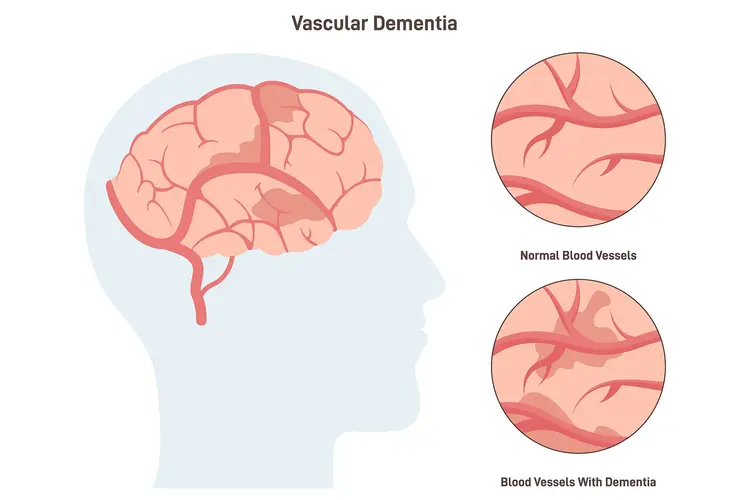

Her core message was simple but powerful. About 45 percent of dementia risk is tied to factors that people can influence. In particular, vascular dementia—the second most common form after Alzheimer’s—is strongly linked to the health of blood vessels in the brain. And what protects the heart, she explained, also protects the brain.

This means that many of the conditions associated with heart disease—high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, and poor circulation—also quietly damage the brain over time. Each constricted artery, each spike in blood pressure, each episode of uncontrolled blood sugar reduces the brain’s ability to receive oxygen and nutrients. Over years and decades, that cumulative strain can manifest as memory loss, confusion, and cognitive decline.

Monitoring blood pressure, she stressed, is not just about avoiding heart attacks or strokes. It is also a crucial step in preserving long-term brain function. Elevated blood pressure in midlife is one of the strongest predictors of dementia in later years, yet it often goes unnoticed because it produces few immediate symptoms.

But managing medical risk factors is only part of the story. The expert outlined three lifestyle changes that, when practiced consistently, can dramatically reduce the likelihood of developing dementia.

The first is regular physical exercise.

She advised engaging in moderate to vigorous physical activity at least three times a week—enough to raise the heart rate and leave a person slightly out of breath. This is not about extreme athletic performance. A brisk walk, cycling, swimming, or a fitness class can all be effective.

Exercise improves blood flow throughout the body, including the brain. It helps regulate blood pressure, reduces inflammation, and encourages the growth of new neural connections. Studies show that physically active individuals maintain better memory and executive function as they age, and that exercise can even slow cognitive decline in those already experiencing early symptoms.

The second pillar is mental stimulation.

Crucially, this does not mean endless brain-training apps or crossword puzzles—although those can help. Mental exercise can be anything that challenges the mind and introduces novelty. Learning a new language, picking up a musical instrument, reading complex material, engaging in strategy games, or mastering a new skill all qualify.

The brain thrives on challenge. When people stretch their thinking, they strengthen the neural networks that support memory, reasoning, and adaptability. Over time, this builds what scientists call “cognitive reserve”—a kind of mental resilience that allows the brain to function effectively even in the presence of disease-related changes.

The third change is dietary.

A brain-protective diet emphasizes vegetables, fruits, whole foods, and fresh ingredients, while minimizing ultra-processed products and excessive sugar. Diets rich in fiber, antioxidants, healthy fats, and essential nutrients reduce inflammation and support vascular health.

Highly processed foods, on the other hand, are often loaded with salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats that contribute to obesity, diabetes, and high blood pressure—all of which increase dementia risk. The brain is metabolically demanding, consuming a significant share of the body’s energy. Poor nutrition starves it of what it needs to maintain and repair itself.

Together, these three habits—movement, mental challenge, and healthy eating—form a powerful defense against cognitive decline.

Midway through her appearance, the expert was identified as Professor Catherine Mummery, a leading figure in dementia research and clinical neurology. She emphasized that these changes benefit not only those at risk of vascular dementia but people vulnerable to any form of cognitive impairment.

“These things together,” she explained, “really help in terms of reducing your risk of getting any form of dementia, not just vascular dementia.”

Her message reframes dementia prevention as a lifelong process rather than a reaction to symptoms. Many people assume that by the time memory problems appear, it is already too late. In reality, the foundations of brain health are laid decades earlier. The choices made in one’s 30s, 40s, and 50s often determine cognitive resilience in later life.

Organizations focused on dementia echo this view. In addition to exercise, mental stimulation, and diet, they recommend reducing alcohol intake, quitting smoking, and carefully managing long-term conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. Hearing protection, social engagement, and adequate sleep are also emerging as important contributors to brain health.

What makes this guidance particularly powerful is its accessibility. These are not expensive medical interventions or experimental therapies. They are daily habits within reach of most people.

Even small changes can compound over time. A weekly routine of walks becomes a cardiovascular safeguard. A hobby that stretches the mind becomes a shield against decline. A shift away from processed foods becomes an investment in future independence.

Dementia remains a complex and multifaceted illness, and not every case can be prevented. Genetics, rare neurological conditions, and unpredictable biological factors will always play a role. But the growing evidence makes one point unmistakably clear: dementia is not simply an inevitable consequence of aging.

For millions, it may be delayed, softened, or avoided entirely through conscious choices made long before the first symptom appears.

In that sense, the message is both sobering and hopeful. The burden of dementia is immense, affecting families, healthcare systems, and entire societies. Yet within that burden lies opportunity—the chance to change trajectories, preserve independence, and extend years of clear thinking and meaningful connection.

The brain, like the heart, responds to care. And the habits that protect it begin today.

Emily Johnson is a critically acclaimed essayist and novelist known for her thought-provoking works centered on feminism, women’s rights, and modern relationships. Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Emily grew up with a deep love of books, often spending her afternoons at her local library. She went on to study literature and gender studies at UCLA, where she became deeply involved in activism and began publishing essays in campus journals. Her debut essay collection, Voices Unbound, struck a chord with readers nationwide for its fearless exploration of gender dynamics, identity, and the challenges faced by women in contemporary society. Emily later transitioned into fiction, writing novels that balance compelling storytelling with social commentary. Her protagonists are often strong, multidimensional women navigating love, ambition, and the struggles of everyday life, making her a favorite among readers who crave authentic, relatable narratives. Critics praise her ability to merge personal intimacy with universal themes. Off the page, Emily is an advocate for women in publishing, leading workshops that encourage young female writers to embrace their voices. She lives in Seattle with her partner and two rescue cats, where she continues to write, teach, and inspire a new generation of storytellers.