A powerful examination of how unconscious prejudice in healthcare can have deadly consequences, and one physician’s journey toward redemption.

Chapter 1: The Night That Changed Everything

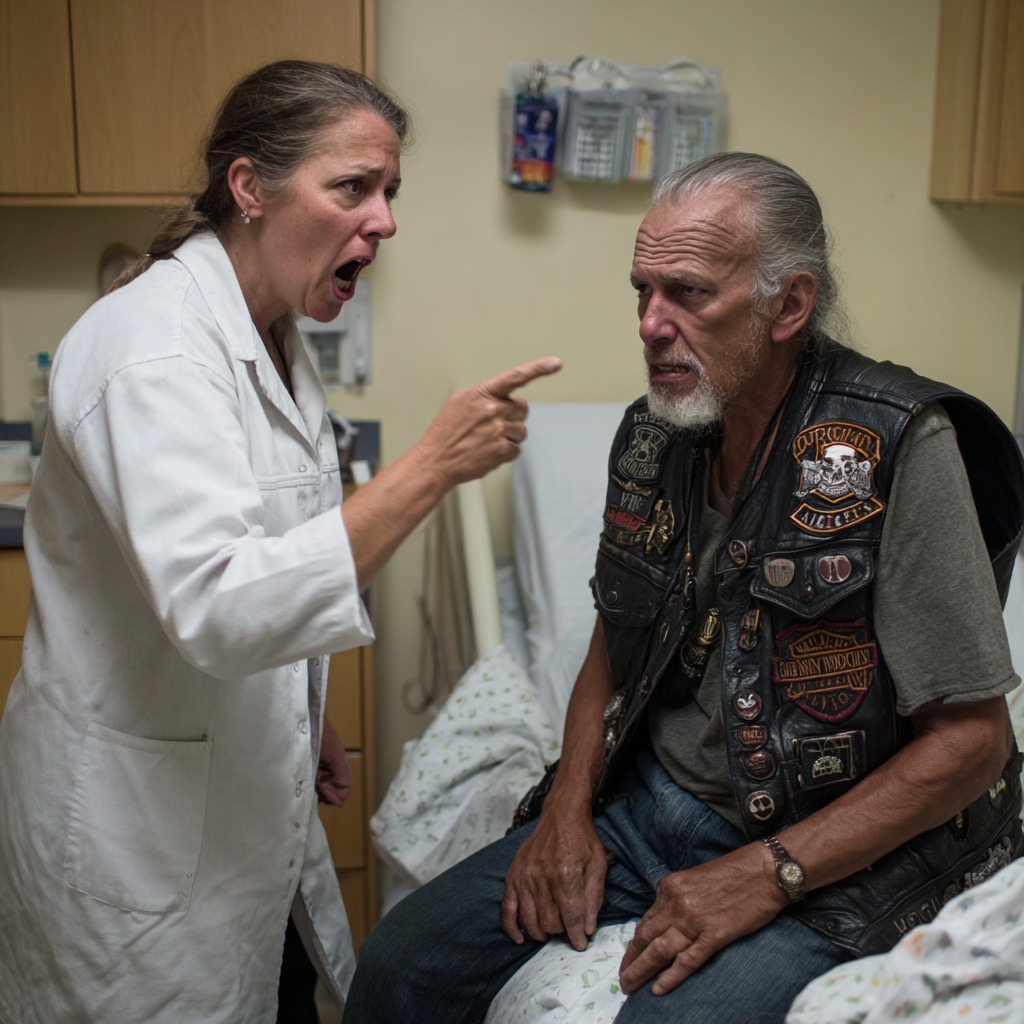

The fluorescent lights of the emergency department cast their harsh glow across another typical Saturday night shift. As Dr. Sarah Mitchell, I had seen it all during my eight years in emergency medicine—overdoses, accidents, domestic violence, and the endless parade of people seeking narcotics under the guise of pain management. At thirty-four, I prided myself on being able to spot drug-seeking behavior from across the room.

It was 2:17 AM when William Morrison limped through the automatic doors of St. Catherine’s Medical Center. Everything about him screamed trouble to my experienced eye: the leather motorcycle vest adorned with patches, the gray ponytail tied back with a rubber band, the work boots that had seen better decades, and the general appearance of someone who lived life on the margins of polite society.

“Another motorcycle accident looking for pills,” I muttered to Nurse Patricia Williams, who had been working emergency medicine longer than I had been alive. She handed me the intake clipboard with a knowing look that suggested she shared my assessment.

“Sixty-five-year-old male,” Patricia reported in her crisp, professional voice. “Motorcycle collision three days ago. Chief complaint is chest pain, rating it seven out of ten. Says the pain is getting worse instead of better.”

I reviewed the basic information with practiced skepticism. Three days after the accident, he was finally seeking medical attention? Classic drug-seeking pattern. Wait until the weekend when younger, presumably more naive physicians were on duty. Come in with subjective complaints that couldn’t be easily verified. Claim escalating pain that required pharmaceutical intervention.

“Put him in examination bay four,” I instructed, already planning the brief encounter that would send him home with recommendations for over-the-counter pain relief and a lecture about emergency room utilization.

William Morrison—the intake form listed him as “Tank” in parentheses—sat hunched on the examination table when I finally entered his cubicle forty-five minutes later. I had deliberately prioritized other cases, a common strategy for managing drug-seekers who might grow impatient and leave if forced to wait.

His appearance was exactly what I expected: weathered face that spoke of decades working outdoors, hands stained with motor oil and callused from manual labor, and that unmistakable leather vest that marked him as part of motorcycle culture I neither understood nor respected.

“Mr. Morrison,” I began, not bothering to mask my skepticism, “you’re reporting chest pain from a motorcycle accident that occurred three days ago. Can you explain why you waited so long to seek medical attention?”

He looked up at me with gray eyes that held an expression I should have recognized as genuine distress but instead interpreted as the calculating look of someone crafting a convincing story.

“Couldn’t afford to miss work, Doc,” he said quietly, his voice carrying the slight breathlessness that should have been my first major warning sign. “Thought it was just bruised ribs at first. But it keeps getting worse, and now I’m having trouble breathing.”

“And what specifically are you hoping I can do for you tonight?” I asked, my tone making it clear that I suspected his true motives.

His jaw tightened slightly—a reaction I misinterpreted as frustration at being questioned rather than the desperate plea of someone genuinely suffering. “I don’t want pills,” he said firmly. “I want to know why I can’t catch my breath. Why it feels like something’s tearing inside my chest.”

But I had already reached my conclusion. The leather vest, the delayed presentation, the subjective complaints that would be difficult to verify—every element fit the profile I had constructed in my mind of the drug-seeking patient. In my eight years of emergency medicine, I had become convinced of my ability to identify these cases with scientific precision.

Chapter 2: The Fatal Assessment

What I failed to see—what my prejudice blinded me to—was a man genuinely struggling with a life-threatening condition. William Morrison had spent three days trying to work through escalating pain because missing even a single day meant his disabled wife wouldn’t have money for her essential medications. His motorcycle wasn’t a symbol of rebellious lifestyle; it was his only transportation to the construction job that barely covered their mounting medical expenses.

I performed what I considered an appropriately thorough examination, though in retrospect, it was cursory at best. I deliberately pressed harder than necessary when palpating his ribs, expecting the exaggerated response that would confirm my suspicions. When he merely winced without crying out, I marked it as another point against him in my prejudiced assessment.

“Appears to be bruised ribs from your accident,” I announced with the confidence of someone who had already decided the diagnosis before entering the room. “Over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medication should provide adequate relief. Rest when possible.”

“Doctor, something’s really wrong,” Morrison insisted, his voice carrying the strain of someone fighting for each breath. “I’ve had broken ribs before—construction accidents, you know. This is different. This is inside, like something’s bleeding.”

The accuracy of his self-diagnosis should have given me pause. Instead, I interpreted it as evidence of someone who had researched his symptoms online to create a more compelling case for prescription painkillers.

“Mr. Morrison,” I replied with barely concealed condescension, “I’ve been practicing emergency medicine for eight years. I believe I can distinguish between soft tissue injury and more serious trauma. You walked into this emergency department under your own power. Your vital signs are stable. You’re experiencing exactly what one would expect after a motorcycle accident.”

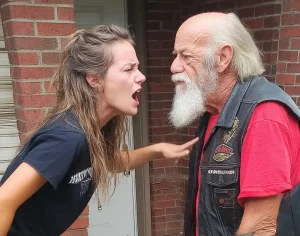

I saw the flash of anger in his eyes, quickly suppressed by what I now understand was sheer exhaustion from the effort of breathing. “You’re making assumptions about me because of how I look,” he said quietly. “Because I ride a motorcycle. Because I work with my hands.”

“I’m making medical decisions based on clinical presentation and professional experience,” I lied, knowing even as I spoke that my judgment was clouded by every stereotype I held about motorcycle culture and blue-collar workers.

“Mr. Morrison, emergency departments exist to treat genuine emergencies. Your condition doesn’t meet those criteria.”

As I turned to leave, Morrison’s hand caught my white coat. His grip was surprisingly weak—another warning sign I completely ignored in my rush to judgment.

“Please,” he said, his voice barely above a whisper. “Just run some basic tests. I’ll pay cash if insurance coverage is the issue. CT scan, blood work, anything. I know something’s wrong inside me.”

I pulled away from his grasp with obvious irritation. “Mr. Morrison, you’re requesting expensive diagnostic procedures for what amounts to muscle strain. This emergency department treats heart attacks, strokes, and trauma cases. Your situation doesn’t warrant our resources.”

Those were the last words I ever spoke to William Morrison as a living patient.

Chapter 3: The Catastrophic Truth

Two hours later, I was suturing a laceration on a skateboarding teenager’s forehead when the trauma alert sounded throughout the emergency department. Paramedics crashed through the doors with a patient in full cardiac arrest, the controlled chaos of emergency medicine swinging into high gear.

“Sixty-five-year-old male found collapsed in the parking lot,” the lead paramedic reported as they transferred their patient to the trauma bay. “Witness states he was attempting to mount his motorcycle when he suddenly collapsed. No pulse for approximately six minutes before we achieved return of spontaneous circulation.”

It wasn’t until they had transferred the patient to our trauma table that I saw his face clearly. William “Tank” Morrison. The “drug-seeker” I had dismissed less than two hours earlier. The man whose desperate pleas I had ignored with professional arrogance.

“I need portable ultrasound immediately,” I shouted, my hands already moving through the familiar choreography of resuscitation, though my mind was reeling with the implications of what I was seeing.

The ultrasound revealed what any competent physician should have suspected hours earlier: massive internal bleeding consistent with a ruptured spleen. Morrison had been slowly bleeding to death while I lectured him about appropriate emergency room utilization.

A simple CT scan would have identified the injury immediately. Basic blood work would have revealed his dropping hemoglobin levels. Any diagnostic test beyond my prejudiced visual assessment would have saved his life.

We worked frantically for fifty-seven minutes. I performed an emergency thoracotomy, manually massaging his failing heart while the trauma team pushed unit after unit of blood into his exsanguinating body. But physiologically, it was far too late. Morrison had been compensating for internal bleeding for days until his cardiovascular system finally collapsed.

Dr. Robert Harrison, our chief trauma surgeon, reviewed the case with barely contained professional disgust. “Massive hemoperitoneum secondary to delayed splenic rupture,” he announced to the gathered team. “Patient was likely bleeding internally for days, compensating until complete cardiovascular collapse. This should have been identified on initial presentation.”

I couldn’t find my voice to respond. The discharge paperwork I had begun earlier still lay on the nursing station counter, with “drug-seeking behavior” written in my handwriting under the clinical assessment section.

Chapter 4: Facing the Consequences

The hospital waiting room had transformed into something I had never seen before: dozens of leather-clad men and women, ranging in age from their twenties to their seventies, all bearing the same patches and insignia that marked them as members of Morrison’s motorcycle club. They had been arriving steadily as word of their brother’s condition spread through their community.

At the center of this gathering sat a woman in a wheelchair, oxygen cannula in her nose, hands trembling with what I recognized as advanced Parkinson’s disease. This was clearly Morrison’s wife, the disabled woman he had been working to support despite his own deteriorating health.

When I finally emerged from the trauma bay, still wearing surgical scrubs stained with Morrison’s blood, the leather-clad crowd fell silent. Their expectant faces turned toward me, and I realized I was about to deliver the worst possible news to people who had every reason to hold me responsible.

“I’m Dr. Mitchell,” I began, my voice cracking with the weight of what I had to say. “I’m very sorry. We did everything medically possible, but Mr. Morrison’s injuries were too severe. He passed away despite our best efforts.”

Morrison’s wife—I learned later her name was Linda—looked at me with eyes that held more dignity than I deserved. “He was here earlier,” she said quietly. “Said the doctor wouldn’t run any tests. Sent him home.”

A younger club member, whose vest identified him as “Priest,” stepped forward. “Tank said the doc took one look at his patches and decided he was just looking for drugs. Wouldn’t even listen to him.”

The accusation hung in the air like a physical presence. I could have denied it, hidden behind medical terminology and defensive explanations. I could have claimed that Morrison’s presentation wasn’t concerning enough to warrant aggressive testing. But William Morrison deserved better treatment in death than I had given him in life.

“I failed your husband,” I said, addressing Linda Morrison directly. “I made assumptions based on his appearance rather than his medical complaints. He asked me to run tests, begged me to investigate his symptoms further. I refused because I had predetermined that he was seeking narcotics.”

The silence that followed was deafening. These people—who I had mentally categorized as dangerous and unpredictable—stood in stunned grief, processing that their friend and brother had died because a physician couldn’t see past leather and motorcycle patches.

Chapter 5: Learning Who William Morrison Really Was

In the days following Morrison’s death, I learned the truth about the man I had killed through my prejudice. William “Tank” Morrison was a decorated Iraq War veteran who had served two combat tours and earned a Purple Heart for injuries sustained while saving fellow soldiers. Despite being eligible for disability benefits, he had continued working construction jobs to support his wife’s extensive medical needs.

The motorcycle club he belonged to, the Iron Hearts MC, was primarily composed of veterans and first responders who dedicated significant time and resources to charitable causes. They organized annual toy drives for disadvantaged children, raised funds for veterans’ families facing financial hardship, and provided escorts for military funerals. Morrison himself had been instrumental in establishing a scholarship fund for children of fallen service members.

The leather vest I had judged so harshly was covered with patches representing charitable rides, memorial services for deceased veterans, and community service projects. Each insignia told the story of a life dedicated to helping others—the complete opposite of my assumptions about motorcycle culture.

The accident that ultimately killed Morrison hadn’t even been his fault. Three days earlier, a teenager texting while driving had sideswiped Morrison’s motorcycle, sending him into a roadside barrier. Despite the impact, Morrison had managed to ride his damaged bike home, not wanting to leave it on the roadside where it might be vandalized or stolen.

Chapter 6: The Funeral That Changed My Perspective

I attended Morrison’s funeral, though I questioned my right to be there. The service was held at a veteran’s cemetery, with hundreds of motorcycles lining the access roads. The procession included riders from multiple states, all coming to pay respects to a man they considered a brother and role model.

The eulogy, delivered by the Iron Hearts MC president, painted a picture of someone I wish I had taken the time to know. Morrison had donated blood every eight weeks for over thirty years, accumulating enough donations to save hundreds of lives. He had mentored dozens of young veterans struggling with the transition to civilian life. He had never met a stranger and never passed someone in need without offering assistance.

Linda Morrison approached me after the service, moving slowly in her wheelchair but with unmistakable determination. I expected anger, threats, perhaps even violence from the hundreds of bikers who surrounded her. Instead, she handed me something from her purse—Morrison’s wallet, still sealed in the hospital’s personal effects bag.

“Look inside,” she said simply.

Along with photographs of grandchildren and his veteran’s identification card was a blood donor card showing Morrison as a “gallon club” member, having donated over 128 pints of blood during his lifetime. There was also a signed organ donor card, though his internal injuries had made that final act of generosity impossible.

“He saved lives,” Linda said quietly. “That’s what Tank did. He saved lives through his blood donations, his charity work, his brotherhood with other veterans. And you couldn’t save his because you couldn’t see past the leather.”

Chapter 7: Professional Reckoning and Personal Transformation

The hospital administration moved quickly to manage the legal and public relations implications of Morrison’s death. They offered the standard legal settlements, implemented new policies about patient assessment protocols, and arranged sensitivity training for all emergency department staff. But none of these institutional responses could address the fundamental failure of my professional judgment.

I submitted my resignation from emergency medicine two weeks after Morrison’s funeral, not because the hospital demanded it, but because I could no longer trust my ability to assess patients objectively. The realization that I had likely made similar prejudicial judgments about other patients was devastating to my professional identity and personal ethics.

The transition to addiction medicine was intentional. I began working at a treatment facility that served exactly the population I had previously dismissed: blue-collar workers, veterans, motorcyclists, and others whose appearance or lifestyle had triggered my unconscious biases. Many of my patients had developed substance use disorders after legitimate injuries, prescribed opioids by physicians who then abandoned them when dependency developed.

Each leather vest that entered my office served as a reminder of William Morrison and the night I let my prejudices override my medical training. I learned to see the individuals behind the external appearances that had once triggered my assumptions: the veteran struggling with chronic pain from combat injuries, the construction worker whose back surgery had led to prescription drug dependency, the motorcycle enthusiast whose accident had initiated a cycle of pain and inadequate treatment.

Chapter 8: The Morrison Memorial Foundation

Linda Morrison established a foundation in her husband’s memory, dedicated to educating healthcare professionals about unconscious bias in medical settings. The Iron Hearts MC began organizing annual memorial rides that concluded at hospitals throughout the region, where they distributed educational materials about respectful patient treatment regardless of appearance or social status.

The foundation’s research revealed that Morrison’s experience was far from unique. Patients who appeared to be from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, particularly those with visible tattoos or unconventional clothing, received significantly less thorough medical evaluations and were more likely to be dismissed as drug-seekers even when presenting with legitimate medical emergencies.

These findings led to the development of standardized assessment protocols designed to minimize the impact of provider bias on clinical decision-making. Medical schools began incorporating unconscious bias training into their curricula, and emergency departments implemented blind assessment procedures for certain types of cases.

Chapter 9: Living with the Consequences

Every month on the anniversary of Morrison’s death, I observe a private memorial. I review his medical records, remind myself of the warning signs I ignored, and recommit to the principle that every patient deserves thorough, unprejudiced medical assessment regardless of their appearance or social status.

The Iron Hearts MC continues their monthly memorial ride, concluding at the hospital where Morrison died. Linda Morrison leads the procession on her specially adapted three-wheeled motorcycle, oxygen tank secured behind her seat, serving as a living reminder of what her husband died trying to protect.

I watch these rides from across the street, maintaining the distance that my failure has earned. I don’t deserve to join their brotherhood or benefit from their forgiveness, but I bear witness to their continued advocacy for improved healthcare equity.

The waiting room where Morrison’s friends and family learned of his death now displays a plaque dedicating the space to his memory. The inscription reads: “William ‘Tank’ Morrison: Veteran, Blood Donor, Community Servant. In memory of a man who gave his life saving others, and whose death teaches us to see beyond appearances to the humanity within.”

Chapter 10: Lessons for the Medical Community

Morrison’s death represents a systemic failure that extends far beyond individual prejudice. Healthcare institutions must acknowledge that unconscious bias affects clinical decision-making at every level, from triage assessment to diagnostic testing to treatment planning.

The most effective interventions combine individual awareness training with structural changes that reduce opportunities for bias to influence patient care. These include:

Standardized Assessment Protocols: Implementing evidence-based clinical decision rules that minimize subjective judgment in initial patient evaluation.

Blind Review Procedures: Having clinical cases reviewed without knowledge of patient demographics or appearance when determining appropriate diagnostic workups.

Cultural Competency Training: Educating healthcare providers about different communities and subcultures to reduce stereotyping and improve communication.

Patient Advocacy Programs: Establishing systems that allow patients to request second opinions or additional testing when they feel their concerns have been dismissed.

Bias Interruption Techniques: Teaching healthcare providers to recognize and counteract their unconscious biases in real-time clinical situations.

Epilogue: The Weight of Memory

I keep Morrison’s obituary in my office desk, not as punishment, but as a daily reminder of the human cost of medical prejudice. The newspaper clipping describes his military service, his charitable work, his role as a devoted husband and grandfather. At the bottom, it mentions his status as an organ donor, though his injuries made that final gift impossible.

The Iron Hearts MC president’s statement, printed below the biographical information, captures the essence of the man I failed to see: “Tank never met a stranger, never passed someone in need, never forgot that beneath the leather, we’re all just humans trying to make it through this life together.”

William Morrison died because I saw a leather vest instead of a patient, motorcycle patches instead of a person, assumptions instead of symptoms. His death certificate lists the medical cause as “exsanguination secondary to delayed splenic rupture,” but the real cause was unconscious bias—a prejudice that transformed a treatable injury into a fatal oversight.

The foundation established in Morrison’s memory has now trained thousands of healthcare providers in bias recognition and mitigation. Their work has undoubtedly saved lives, prevented other families from experiencing the loss that Linda Morrison endures daily. In that sense, Tank Morrison continues to save lives even after his death—a legacy he would have appreciated.

Some medical mistakes can be corrected through continuing education, additional training, or improved protocols. Others can only be carried as permanent reminders of our fallibility and our responsibility to do better. William Morrison’s death belongs to the latter category—a burden I will bear for the remainder of my career and a motivation to ensure that no other patient suffers the same fate due to healthcare provider prejudice.

In medicine, as in life, our assumptions can kill. The leather vest we judge may belong to the very person trying to save lives through blood donations, charity work, and community service. Our responsibility as healthcare providers is to see the human being first, the external appearance never. William Morrison deserved that respect in life. His memory demands that we provide it to every patient who follows.

Understanding and Preventing Medical Bias

William Morrison’s tragic death illustrates the devastating consequences of unconscious bias in healthcare settings. Research demonstrates that medical prejudice based on appearance, social status, race, gender, and other factors significantly impacts patient outcomes across all medical specialties.

The Science of Medical Bias: Studies reveal that healthcare providers, despite their training and ethical commitments, are susceptible to the same unconscious biases that affect decision-making in other professional contexts. These biases can influence everything from pain assessment to diagnostic testing to treatment recommendations.

Common Bias Triggers in Healthcare:

- Physical appearance and clothing choices

- Perceived socioeconomic status

- Race and ethnicity

- Age and gender

- Insurance status

- Previous medical history

- Communication style and education level

The Impact on Patient Care: Research shows that patients from marginalized communities receive less thorough medical evaluations, are less likely to receive appropriate pain management, and experience longer wait times for treatment. These disparities contribute to significant health outcome inequalities across different populations.

Institutional Solutions: Effective bias reduction requires both individual awareness and systemic changes:

Individual Interventions:

- Unconscious bias training for all healthcare staff

- Mindfulness practices to increase self-awareness

- Structured reflection on clinical decision-making

- Cultural competency education

Systemic Interventions:

- Standardized clinical assessment protocols

- Blind case review procedures

- Patient advocacy programs

- Diverse hiring practices

- Community partnership initiatives

The Role of Medical Education: Medical schools and residency programs are increasingly incorporating bias awareness into their curricula, teaching future physicians to recognize and counteract their unconscious prejudices before they impact patient care.

Patient Empowerment: Patients can advocate for themselves by:

- Clearly communicating their concerns

- Requesting second opinions when appropriate

- Bringing advocates to medical appointments

- Understanding their rights to respectful treatment

- Providing feedback about their healthcare experiences

Moving Forward: William Morrison’s story serves as a powerful reminder that healthcare equity requires constant vigilance and ongoing commitment to improvement. Every healthcare provider has a responsibility to examine their biases and work actively to ensure that all patients receive respectful, thorough, and appropriate medical care.

The foundation established in Morrison’s memory continues to work toward a healthcare system where no patient dies because of provider prejudice. Their research and advocacy efforts represent hope that future William Morrisons will receive the care they deserve, regardless of the vest they wear or the motorcycle they ride.

Emily Johnson is a critically acclaimed essayist and novelist known for her thought-provoking works centered on feminism, women’s rights, and modern relationships. Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Emily grew up with a deep love of books, often spending her afternoons at her local library. She went on to study literature and gender studies at UCLA, where she became deeply involved in activism and began publishing essays in campus journals. Her debut essay collection, Voices Unbound, struck a chord with readers nationwide for its fearless exploration of gender dynamics, identity, and the challenges faced by women in contemporary society. Emily later transitioned into fiction, writing novels that balance compelling storytelling with social commentary. Her protagonists are often strong, multidimensional women navigating love, ambition, and the struggles of everyday life, making her a favorite among readers who crave authentic, relatable narratives. Critics praise her ability to merge personal intimacy with universal themes. Off the page, Emily is an advocate for women in publishing, leading workshops that encourage young female writers to embrace their voices. She lives in Seattle with her partner and two rescue cats, where she continues to write, teach, and inspire a new generation of storytellers.