Cinema is often described as a marriage of storytelling and technology. While screenplays and performances carry the narrative, it is cinematography—the art of capturing images on screen—that gives movies their visual soul. Through lighting, framing, movement, and color, cinematographers translate words into emotions, ideas, and unforgettable images. From the sweeping landscapes of Lawrence of Arabia to the intimate close-ups of Moonlight, cinematography shapes how audiences experience stories, sometimes without them even realizing it.

In this article, we’ll explore what cinematography is, why it matters, and how the visual language of film continues to evolve in both artistic and technological ways.

What Is Cinematography?

At its core, cinematography is the craft of visual storytelling. It encompasses everything that appears within the camera’s frame, as well as the choices made to capture it. Cinematographers—also known as directors of photography (DPs)—work closely with directors to determine the look and feel of a film. Their responsibilities include:

-

Framing and composition: deciding what the audience sees.

-

Lighting: setting mood, depth, and focus.

-

Camera movement: creating rhythm, energy, or intimacy.

-

Lens choice: determining perspective and scale.

-

Color palette: guiding emotion and tone.

Cinematography is not just technical; it is profoundly artistic. It transforms abstract ideas into images that resonate deeply with viewers.

The Power of Framing and Composition

Framing determines how much of a scene the audience sees and where their attention is directed. A wide shot can emphasize isolation, while a tight close-up can convey intimacy or claustrophobia. Directors like Stanley Kubrick mastered symmetrical compositions, creating frames that feel both meticulously calculated and emotionally unsettling. Conversely, handheld and off-center compositions can evoke realism and spontaneity.

Composition is also about storytelling. For example, in The Godfather, Gordon Willis often framed characters in shadow, reinforcing themes of secrecy and power. The placement of objects and characters within a frame subtly communicates hierarchy, relationships, and emotional subtext.

Lighting: Painting With Shadows

If framing is the skeleton of cinematography, lighting is its heartbeat. Light can transform a mundane setting into something magical or foreboding. Classic film noir relied on high-contrast lighting to create mystery, while romantic dramas often employ soft, warm tones to evoke tenderness.

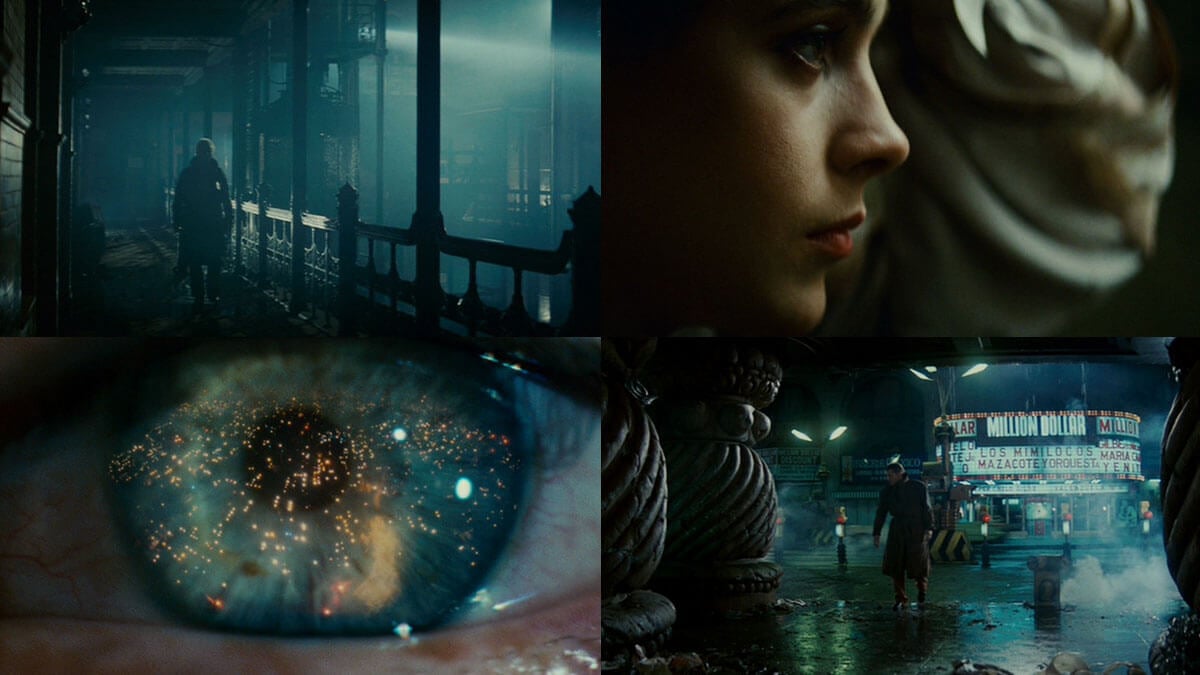

Roger Deakins, one of cinema’s most celebrated cinematographers, is renowned for his mastery of naturalistic lighting. In Blade Runner 2049, he used bold contrasts of neon and shadow to build a futuristic yet melancholic atmosphere. Lighting not only illuminates but also adds layers of meaning—highlighting, concealing, or reshaping what the audience perceives.

Camera Movement: The Dance of Storytelling

How a camera moves through space dramatically influences storytelling. A slow tracking shot can immerse viewers in a character’s journey, while rapid handheld movement can heighten chaos and tension. Consider the long takes of Alfonso Cuarón in Children of Men or the dynamic fight sequences captured by Emmanuel Lubezki in The Revenant. These movements aren’t just spectacle—they place audiences within the action, making them feel like participants rather than observers.

Static shots also carry power. Yasujiro Ozu famously used a still, low camera angle to create a sense of calm observation, allowing viewers to reflect on the subtleties of family life in postwar Japan.

The Emotional Language of Color

Color is one of the most immediately recognizable aspects of cinematography. Bright, saturated palettes often suggest joy or fantasy, while muted tones can convey realism or melancholy. In Schindler’s List, Janusz Kamiński shot primarily in black and white, with a single splash of red serving as a haunting visual motif. Meanwhile, Wes Anderson’s films are known for their meticulous, pastel-colored palettes that reinforce his whimsical style.

Modern cinematography often employs digital color grading, allowing filmmakers to fine-tune mood with precision. A teal-and-orange palette, for instance, has become a Hollywood staple, balancing skin tones with cinematic contrast.

Iconic Cinematographers and Their Legacies

The history of cinema is filled with visionary cinematographers who pushed boundaries and redefined the art form:

-

Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now) — used bold color symbolism to reflect psychological states.

-

Gregg Toland (Citizen Kane) — pioneered deep focus cinematography, keeping multiple planes sharp in one frame.

-

Emmanuel Lubezki (Gravity, Birdman) — known for long takes and natural light, immersing audiences in continuous movement.

-

Rachel Morrison (Mudbound) — the first woman nominated for an Academy Award in cinematography, praised for her atmospheric realism.

Their innovations demonstrate that cinematography is not just craft—it is authorship, leaving an imprint as recognizable as a director’s signature.

The Evolution of Technology

Cinematography has always been shaped by technology. Early films relied on bulky cameras and natural light, while the 20th century saw the introduction of portable cameras, wide-screen formats, and new film stocks. The digital revolution of the 1990s and 2000s transformed cinematography once again, making cameras lighter, more versatile, and more affordable.

Today, drones allow for breathtaking aerial shots, while CGI blends seamlessly with live-action footage. High dynamic range (HDR) enhances contrast and color depth, offering audiences visuals closer to human vision. Yet, despite technological leaps, the essence of cinematography remains unchanged: serving the story.

Cinematography Across Genres

Different film genres call for different visual languages:

-

Horror: Relies on shadows, sudden camera movements, and off-kilter framing to instill fear.

-

Romance: Often uses warm tones and soft lighting to create intimacy.

-

Action: Employs fast cuts, dynamic angles, and kinetic movement to amplify excitement.

-

Documentary: Prioritizes realism, often with handheld cameras and natural light.

A skilled cinematographer adapts their techniques to enhance genre conventions while finding new ways to surprise audiences.

Why Cinematography Matters

Cinematography is often described as “invisible” when done well. Audiences may not consciously notice the choices made, but they feel their effects emotionally. The angle of a shot can make a character seem powerful or vulnerable; the use of shadows can make a setting feel safe or menacing. Without cinematography, movies would lose their emotional resonance and visual poetry.

Moreover, cinematography shapes collective memory. Iconic images—the twin suns of Star Wars: A New Hope, the blood-soaked elevator in The Shining, the floating feather in Forrest Gump—linger in cultural consciousness because of how they were captured, not merely because of what was written on the page.

The Future of Cinematography

As filmmaking continues to evolve, cinematography faces new frontiers. Virtual production, such as the LED “volume” used in The Mandalorian, allows filmmakers to blend real actors with digital environments in real time. Artificial intelligence is being tested to optimize lighting and camera movements. Yet, even with advanced tools, the human touch remains irreplaceable. A machine can replicate technique, but it cannot replace the intuition and artistry that make cinematography so powerful.

Cinematography will continue to bridge the gap between technology and storytelling, ensuring that even in a digital age, films remain deeply human.

Conclusion

Cinematography is the heartbeat of cinema, the bridge between narrative and audience. It is a language that transcends words, communicating through light, color, movement, and composition. From the shadows of classic noir to the glowing worlds of modern digital epics, cinematography defines how stories live in our imagination. While technology will continue to change the tools available, the purpose remains constant: to create images that move us, stay with us, and help us see the world anew.

Sarah Mitchell is a bestselling novelist recognized for her insightful and emotionally resonant stories that explore the complexities of human relationships. Originally from Denver, Colorado, Sarah grew up in a family of teachers who nurtured her curiosity and love for storytelling. She studied psychology at Stanford University, where she became fascinated by the intricacies of human behavior—an interest that would later shape her writing career. Sarah’s novels are praised for their nuanced characters, intricate plots, and ability to capture the subtle tensions that define love, friendship, and family ties. Her breakthrough novel, The Spaces Between Us, became an instant bestseller, lauded for its honest portrayal of strained family relationships and the fragile bonds that hold people together. Since then, she has published several works that continue to captivate audiences around the world. Outside of her writing career, Sarah is passionate about mental health advocacy and often partners with organizations to promote awareness and support for those struggling with emotional well-being. Her personal life is quieter—she enjoys hiking in the Colorado mountains, practicing yoga, and spending time with close friends. With each new book, Sarah Mitchell cements her reputation as a writer who illuminates the beauty and struggles of human connection.