The U.S. Supreme Court has clarified that a key provision of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA), which requires federal courts to dismiss certain previously raised habeas corpus claims, applies exclusively to state prisoners, not federal inmates. The 5-4 decision resolves a long-standing circuit split regarding the scope of AEDPA’s restrictions on second or successive habeas petitions.

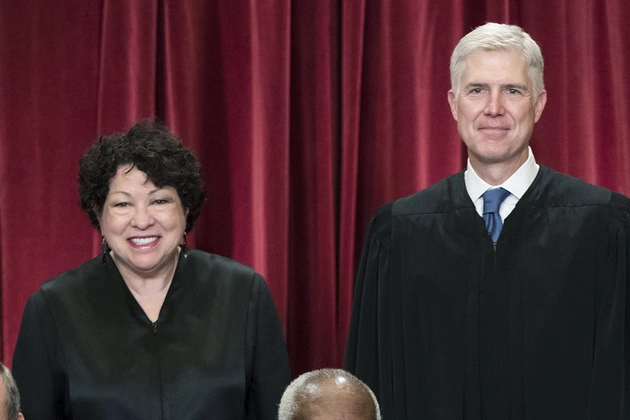

Writing for the majority, Justice Sonia Sotomayor emphasized that Congress has repeatedly drawn distinctions between federal and state prisoners in the structure and language of AEDPA. “AEDPA is replete with examples of Congress treating state and federal prisoners differently,” she wrote, underscoring that the law’s provisions restricting successive habeas claims were intended to address the special procedural posture of state convictions rather than federal ones.

Background and Legal Context

The case arose from the petition of Michael Bowe, a federal inmate who had pleaded guilty in 2008 to multiple offenses, including conspiracy to commit Hobbs Act robbery, attempted Hobbs Act robbery, and discharging a firearm during a “crime of violence” in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c). Over the years, a series of Supreme Court rulings had invalidated the legal basis for Bowe’s firearm conviction. In response, Bowe sought to file a successive habeas corpus petition under 28 U.S.C. § 2255 to challenge his federal sentence.

Bowe encountered a significant barrier: Section 2244(b)(1) of AEDPA requires federal courts to dismiss any claim presented in a “second or successive habeas corpus application under section 2254” if that claim had been raised in a prior application. Section 2254 governs habeas applications filed by state prisoners. Nevertheless, the Eleventh Circuit, one of six circuits to interpret the statute broadly, applied Section 2244(b)(1) to federal inmates’ motions under 28 U.S.C. § 2255, effectively barring Bowe from filing his successive petition.

The split among federal appellate courts was stark. While the Eleventh, Second, Sixth, and other circuits applied the provision to federal prisoners, three circuits, including the Ninth and Fourth, held that the plain text of AEDPA limited the restriction on successive claims exclusively to state prisoners. The divergence had created significant uncertainty about the rights of federal inmates seeking to challenge their convictions after new legal developments.

Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court’s ruling resolves this dispute by siding with Bowe and the circuits that interpreted AEDPA as applicable only to state prisoners. The majority opinion emphasizes that the statute’s plain language and structural context indicate Congress’s intent to differentiate between state and federal postconviction procedures. Federal prisoners, the Court concluded, are not subject to the same restrictions on successive claims under AEDPA that apply to state inmates.

The decision reflects careful attention to both statutory text and legislative history. Congress, the opinion notes, repeatedly included provisions specifically addressing federal prisoners’ access to habeas review, signaling an intent to treat state and federal convictions differently. By limiting Section 2244(b)(1) to state prisoners, the Court restores the ability of federal inmates like Bowe to seek relief in situations where subsequent developments—such as Supreme Court rulings invalidating legal theories underpinning their convictions—warrant reconsideration.

Dissenting Opinion

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the principal dissent, joined fully by Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, and in part by Justice Amy Coney Barrett. The dissent argued that the Court’s majority misread AEDPA’s text and purpose, which, in their view, was designed to impose uniform restrictions on second or successive habeas petitions regardless of whether the petitioner is a state or federal inmate. Gorsuch emphasized the importance of finality in criminal convictions and the risks posed by allowing repeated postconviction challenges, particularly in the federal system, where Congress intended to streamline habeas review.

Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court’s decision carries significant implications for federal inmates seeking to challenge their convictions. Under the ruling, federal prisoners who have already filed a habeas petition may now bring subsequent claims under § 2255 without being automatically barred by AEDPA’s successive-petition restriction. This is particularly consequential for inmates like Bowe, whose firearm convictions had been invalidated by later Supreme Court decisions. The ruling ensures that federal prisoners can access the courts to correct potential injustices even after previous petitions have been denied.

For federal courts, the decision clarifies a previously murky area of habeas law. Judges must now apply Section 2244(b)(1) only to petitions filed by state prisoners, while federal inmates’ § 2255 petitions are evaluated on their own merits. The ruling is expected to reduce procedural confusion in the lower courts and prevent inconsistent application of the law across different circuits.

Broader Legal and Policy Context

AEDPA, enacted in 1996 in the wake of concerns about excessive delays in postconviction review, imposed strict limits on successive habeas petitions to promote finality and efficiency in the criminal justice system. The law was designed primarily to address state convictions, where multiple rounds of habeas petitions were seen as a significant procedural burden. In contrast, Congress provided federal prisoners with distinct avenues for postconviction relief, recognizing the different legal framework governing federal offenses.

By drawing a clear distinction between state and federal habeas petitions, the Supreme Court reaffirmed a key principle of statutory interpretation: the importance of adhering to Congress’s explicit language and intent. The ruling demonstrates judicial attention to procedural fairness, ensuring that federal inmates retain access to remedies when legal circumstances change after their convictions have become final.

Representation and Case Details

Michael Bowe was represented by the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center and the Southern District of Florida Federal Public Defender’s Office. The Supreme Court case is cited as Bowe v. United States, U.S., No. 24-5438. The government did not contest Bowe’s interpretation of Section 2244(b)(1) but questioned the Court’s jurisdiction to hear the case. The Court appointed Kasdin M. Mitchell of Kirkland & Ellis to argue in favor of the Eleventh Circuit’s approach during oral arguments.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision resolves a longstanding circuit split, clarifying that the limitations imposed by AEDPA on successive habeas petitions apply solely to state prisoners. The ruling restores federal inmates’ ability to pursue claims challenging their convictions under § 2255, ensuring that new legal developments, such as the invalidation of key statutory provisions or judicial interpretations, can be addressed in the federal courts. While the dissent raised concerns about finality and the potential burden on federal courts, the majority emphasized the statute’s clear language and the differential treatment of state and federal prisoners.

For federal inmates and their advocates, the ruling is a significant victory, reaffirming access to the courts and the ability to seek redress when new legal issues arise. For the federal judiciary, it provides clarity in applying AEDPA and eliminates confusion stemming from conflicting circuit interpretations. In practical terms, the decision may open the door for a number of federal prisoners to seek relief based on evolving legal standards, particularly in cases involving firearm-related convictions and other areas where Supreme Court precedent has shifted over time.

By confirming that AEDPA’s successive-petition bar is limited to state prisoners, the Supreme Court has provided a definitive answer on an issue that had divided the lower courts for years, reinforcing both statutory clarity and procedural fairness in postconviction review for federal inmates.

Emily Johnson is a critically acclaimed essayist and novelist known for her thought-provoking works centered on feminism, women’s rights, and modern relationships. Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Emily grew up with a deep love of books, often spending her afternoons at her local library. She went on to study literature and gender studies at UCLA, where she became deeply involved in activism and began publishing essays in campus journals. Her debut essay collection, Voices Unbound, struck a chord with readers nationwide for its fearless exploration of gender dynamics, identity, and the challenges faced by women in contemporary society. Emily later transitioned into fiction, writing novels that balance compelling storytelling with social commentary. Her protagonists are often strong, multidimensional women navigating love, ambition, and the struggles of everyday life, making her a favorite among readers who crave authentic, relatable narratives. Critics praise her ability to merge personal intimacy with universal themes. Off the page, Emily is an advocate for women in publishing, leading workshops that encourage young female writers to embrace their voices. She lives in Seattle with her partner and two rescue cats, where she continues to write, teach, and inspire a new generation of storytellers.