The Supreme Court has agreed to decide a case that pits decades-old federal law against the realities of modern internet tracking, advertising, and online media consumption. At issue is how a statute written for the era of VHS tapes applies to today’s web pages, streaming clips, and invisible data transfers that occur when users watch video content online.

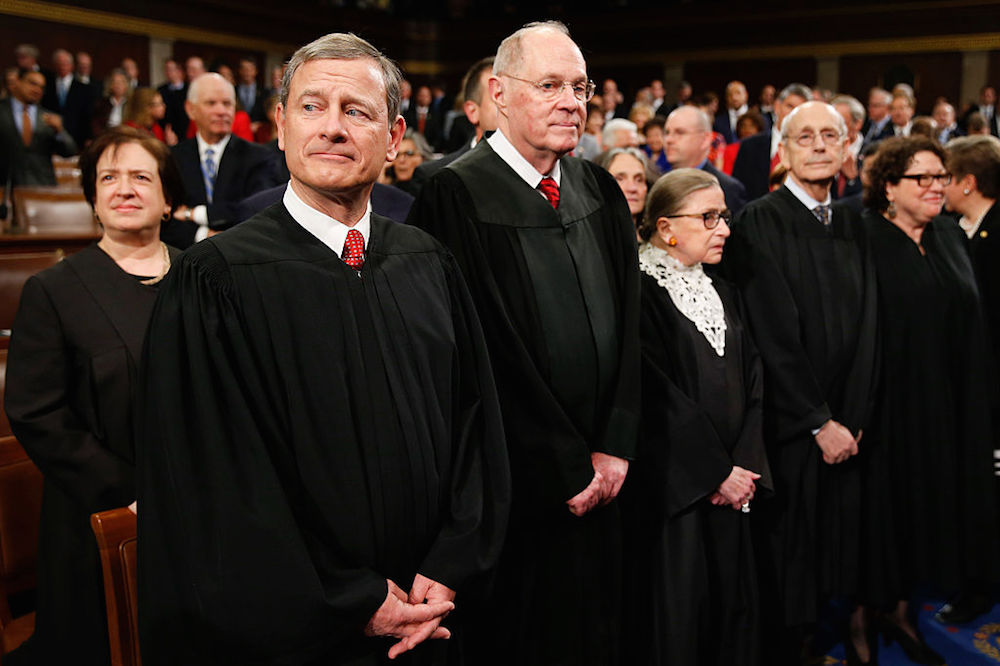

The dispute arrives at the Court after years of conflicting rulings in the lower courts. Federal appeals judges have split on whether people who watch videos on websites—often for free—qualify for protections under a federal privacy law enacted in 1988. That disagreement has created uncertainty for consumers and companies alike, prompting the justices to step in and set a national rule.

The case centers on a familiar modern scenario: a user visits a website, watches a video, and—without any obvious notification—information about that viewing activity is shared with a third party, such as a social media platform or advertising network. The legal question is whether that kind of data sharing violates federal law, and if so, who is protected.

A Law Born in a Different Era

The statute at the heart of the case is the Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA), passed by Congress in response to a specific scandal. In the late 1980s, a newspaper obtained and published the video rental history of a Supreme Court nominee. The public backlash was swift, and lawmakers responded by making it illegal for video rental stores to disclose customers’ viewing histories without consent.

At the time, the law was straightforward. A “video tape service provider” was a physical store, a “consumer” was someone who rented or bought tapes, and “personally identifiable information” was a list of titles connected to a name. Few imagined that, decades later, courts would be asked to apply the same language to streaming clips, embedded players, tracking pixels, and social media identifiers.

As video moved online, however, the VPPA quietly gained new relevance. Plaintiffs began arguing that websites sharing video-viewing data with third parties were violating the law, even if no money changed hands and no physical media was involved. Defendants countered that Congress never intended the VPPA to regulate the modern internet.

The Case That Forced the Court’s Hand

The lawsuit before the Supreme Court arose after a website user alleged that a media company shared information about the videos he watched with a social media platform. According to the complaint, when the user watched videos while logged into his social media account, the website transmitted a unique identifier along with details about the videos viewed.

The user argued that this data amounted to “personally identifiable information” and that he qualified as a protected “consumer” under the VPPA. The company disagreed, maintaining that the law applies only to people who rent or subscribe to video services in a more traditional sense.

A federal appeals court sided with the company, dismissing the lawsuit on the grounds that the user was not a “consumer” as defined by the statute. Other appellate courts, however, have reached the opposite conclusion in similar cases, holding that online users can fall within the law’s protections even when content is free.

That conflict—known as a circuit split—made Supreme Court review increasingly likely. With businesses and consumers subject to different rules depending on where a case was filed, the justices agreed to intervene.

What the Justices Will Decide

The Court’s review will focus on several interrelated questions that carry broad implications:

-

Who counts as a “consumer”? Does the term include anyone who watches online video content, or only those who pay or formally subscribe?

-

What qualifies as “personally identifiable information”? Is a unique digital identifier enough if it can be linked to a specific person through a third party?

-

Who is a “video service provider” today? Does the label extend beyond streaming platforms to news sites, sports pages, and other websites that host video clips?

How the Court answers these questions will determine whether the VPPA becomes a powerful tool for regulating modern data practices or remains largely confined to its original, analog context.

Why the Outcome Matters to Consumers

For privacy advocates, the case is about more than a technical definition. They argue that video-viewing habits can reveal sensitive information about a person’s interests, beliefs, and behavior. When combined with digital identifiers, that data can be used to build detailed profiles without a user’s knowledge or consent.

Supporters of a broader interpretation say the harm is comparable to the original concern that motivated Congress in 1988. Back then, it was troubling that someone’s movie choices could be exposed. Today, they argue, the scale and sophistication of data collection make the risk even greater.

If the Court sides with consumers, websites may be forced to rethink how they share data related to video content. Companies could face increased litigation and may need to implement clearer consent mechanisms or limit third-party tracking.

The Stakes for Businesses and Publishers

Media companies and online platforms warn that an expansive reading of the VPPA could have sweeping consequences. Many websites rely on advertising revenue tied to user data, including engagement with video content. A ruling that treats routine data sharing as unlawful could disrupt established business models.

Industry groups argue that Congress, not the courts, should update privacy laws to address modern technology. They contend that stretching old statutes beyond their original purpose creates uncertainty and exposes companies to liability for practices that were never clearly prohibited.

Some also caution that the VPPA includes statutory damages, which can add up quickly in class-action lawsuits. A single adverse ruling could trigger a wave of litigation against publishers large and small.

A Broader Pattern at the Court

The case fits into a larger trend at the Supreme Court: deciding how to apply old laws to new technologies. In recent years, the justices have confronted similar questions involving cell phone searches, location tracking, and digital communications.

Sometimes the Court has taken a narrow approach, emphasizing the limits of statutory text. In other instances, it has acknowledged that technological change requires a more flexible interpretation to protect constitutional or statutory rights.

Observers are divided on which path the Court will take here. Some expect a cautious ruling that avoids dramatically expanding liability. Others believe the justices may signal that privacy protections should not evaporate simply because technology has evolved.

Timing and What Comes Next

The Court’s decision to hear the case does not resolve the underlying dispute. Oral arguments are expected during an upcoming term, with a final ruling likely months later. During arguments, justices will press lawyers on how far the law should extend and what consequences their interpretations would have.

Questions from the bench may offer clues. A focus on statutory text could favor a narrower outcome, while concerns about real-world data practices might suggest a broader view of consumer protection.

Regardless of the result, the ruling will set a precedent nationwide, replacing the current patchwork of interpretations with a single standard.

Implications Beyond This Case

The decision could influence how courts interpret other privacy-related statutes enacted before the internet age. It may also shape ongoing debates in Congress over whether comprehensive federal privacy legislation is needed.

For now, companies, consumers, and regulators are watching closely. The Court’s unanimous decision to take the case underscores its significance—and the recognition that the clash between old laws and new technology can no longer be ignored.

When the justices finally rule, they will not only decide the fate of one lawsuit but also clarify how much protection Americans can expect for their digital viewing habits in an increasingly connected world.

Emily Johnson is a critically acclaimed essayist and novelist known for her thought-provoking works centered on feminism, women’s rights, and modern relationships. Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Emily grew up with a deep love of books, often spending her afternoons at her local library. She went on to study literature and gender studies at UCLA, where she became deeply involved in activism and began publishing essays in campus journals. Her debut essay collection, Voices Unbound, struck a chord with readers nationwide for its fearless exploration of gender dynamics, identity, and the challenges faced by women in contemporary society. Emily later transitioned into fiction, writing novels that balance compelling storytelling with social commentary. Her protagonists are often strong, multidimensional women navigating love, ambition, and the struggles of everyday life, making her a favorite among readers who crave authentic, relatable narratives. Critics praise her ability to merge personal intimacy with universal themes. Off the page, Emily is an advocate for women in publishing, leading workshops that encourage young female writers to embrace their voices. She lives in Seattle with her partner and two rescue cats, where she continues to write, teach, and inspire a new generation of storytellers.