El Salvador’s president has escalated an increasingly tense international debate over crime, incarceration, and immigration, issuing a provocative response to criticism from a prominent U.S. political figure over the country’s notorious mega-prison. The exchange has drawn global attention, highlighting deep divisions over how governments confront organized crime, human rights concerns, and the handling of deported migrants.

At the center of the dispute is the Terrorism Confinement Center, widely known as CECOT, a massive maximum-security prison built as the cornerstone of El Salvador’s crackdown on gangs. The facility has become a symbol of the government’s hardline approach to public safety, housing tens of thousands of inmates accused or convicted of gang-related crimes. In recent months, it has also received migrants deported from the United States, some of whom have been labeled as members of transnational criminal organizations.

The Salvadoran government has consistently defended CECOT as a necessary response to decades of violence that once made the country one of the most dangerous in the world. Officials point to dramatic reductions in homicide rates and gang activity as evidence that the strategy is working. Critics, however, argue that the prison represents an extreme erosion of civil liberties, raising alarms about due process, overcrowding, and allegations of mistreatment.

Those criticisms intensified after a documentary circulated online, featuring testimonies from several deported migrants who claimed they were wrongfully labeled as gang members and subjected to harsh conditions. The film quickly gained traction among activists and media organizations, fueling renewed scrutiny of El Salvador’s security policies and its cooperation with U.S. immigration authorities.

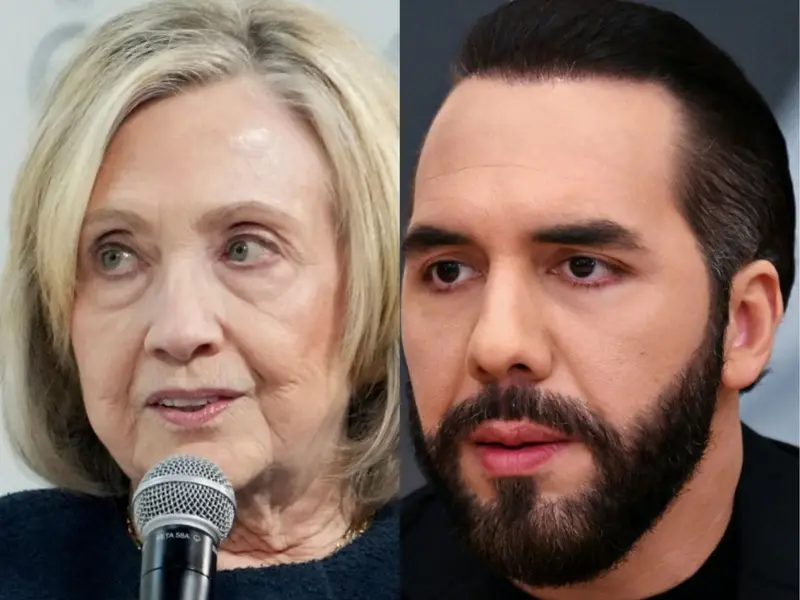

It was in response to this renewed attention that President Nayib Bukele delivered one of his most striking public statements to date. Writing on social media, he dismissed the allegations as politically motivated and challenged critics to take responsibility themselves. He declared that if foreign governments and advocacy groups truly believed systemic abuse was occurring, El Salvador would be willing to release its entire prison population — including convicted gang leaders and alleged political prisoners — to any country prepared to accept them. The only condition, he said, was that the transfer must include everyone.

The remark was widely interpreted as both sarcasm and defiance, underscoring Bukele’s frustration with what he views as selective outrage from abroad. Supporters praised the statement as a bold exposure of what they see as hypocrisy, arguing that countries critical of El Salvador’s tactics have struggled to control violent crime themselves. Detractors, meanwhile, accused the president of trivializing serious human rights concerns and using inflammatory rhetoric to silence dissent.

Midway through the unfolding controversy, Hillary Clinton emerged as a focal point after publicly sharing the documentary and amplifying concerns about the treatment of inmates and deportees at CECOT. Her comments framed the issue as one of moral responsibility, questioning whether individuals were being deprived of basic rights without sufficient evidence or legal recourse. The former U.S. secretary of state’s intervention ensured that the dispute would resonate far beyond Central America, quickly becoming a flashpoint in broader ideological battles over law enforcement and immigration.

Bukele’s response went further than a simple rebuttal. He suggested that releasing inmates abroad would also benefit journalists and non-governmental organizations, providing them with thousands of former prisoners to interview. If the alleged abuses were truly widespread, he argued, a larger pool of voices should easily confirm that reality. Until such proof emerged, he said, his administration would remain focused on protecting the rights of ordinary Salvadorans who now live without the constant threat of gang violence.

The president’s stance reflects a broader philosophy that has defined his leadership. Since launching an aggressive state of emergency against gangs, Bukele has prioritized security and public order over international approval. His policies have earned him extraordinary domestic popularity, particularly among citizens who credit him with restoring a sense of safety that had been absent for generations. Streets once controlled by criminal groups have reopened, businesses have expanded, and tourism has rebounded — outcomes his government cites repeatedly when defending its record.

Yet international concern continues to mount. Human rights organizations have documented thousands of arrests carried out under emergency powers, alleging that many detainees have not been formally charged or tried. Families of inmates claim they have little information about their relatives’ whereabouts or health. These concerns have prompted legal challenges in U.S. courts, particularly regarding deported migrants who argue they were denied due process before being sent to El Salvador.

The controversy also intersects with U.S. domestic politics. El Salvador has strengthened its relationship with the Trump administration by agreeing to accept certain deportees that other countries refused to take back. That cooperation has been praised by advocates of tougher immigration enforcement, who see it as a pragmatic solution to dealing with suspected gang members. Critics counter that it risks outsourcing human rights responsibilities to a system with limited oversight.

As the debate intensifies, the clash between Bukele and his critics illustrates a deeper global divide. On one side are leaders and voters who believe extraordinary measures are justified to dismantle violent criminal networks. On the other are those who warn that sacrificing legal safeguards sets a dangerous precedent, regardless of the security gains achieved.

For now, El Salvador shows no sign of retreating from its current path. Bukele has made clear that external pressure will not dictate his policies, particularly when he believes they conflict with the will and safety of his citizens. Whether his dramatic challenge will quiet critics or further inflame the debate remains uncertain, but it has undeniably ensured that the spotlight on CECOT — and on El Salvador’s uncompromising approach to crime — will remain firmly in place.

Emily Johnson is a critically acclaimed essayist and novelist known for her thought-provoking works centered on feminism, women’s rights, and modern relationships. Born and raised in Portland, Oregon, Emily grew up with a deep love of books, often spending her afternoons at her local library. She went on to study literature and gender studies at UCLA, where she became deeply involved in activism and began publishing essays in campus journals. Her debut essay collection, Voices Unbound, struck a chord with readers nationwide for its fearless exploration of gender dynamics, identity, and the challenges faced by women in contemporary society. Emily later transitioned into fiction, writing novels that balance compelling storytelling with social commentary. Her protagonists are often strong, multidimensional women navigating love, ambition, and the struggles of everyday life, making her a favorite among readers who crave authentic, relatable narratives. Critics praise her ability to merge personal intimacy with universal themes. Off the page, Emily is an advocate for women in publishing, leading workshops that encourage young female writers to embrace their voices. She lives in Seattle with her partner and two rescue cats, where she continues to write, teach, and inspire a new generation of storytellers.